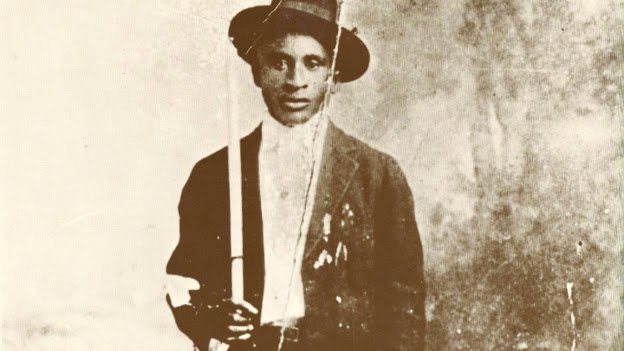

Last summer, the search for Amédé Ardoin seemed to have hit its final dead end. Lawrence Ardoin, a descendant of the legendary Creole accordionist, was working with officials at the state mental institution in Pineville, La. to erect a statue for Amédé, considered by many to be the godfather of zydeco and Cajun music.

But Ardoin is one of 2,469 patients buried in unmarked graves on the hospital grounds. With no way to know which grave holds Amédé, Lawrence Ardoin was giving up.

But the effort to memorialize Amédé again has new life. The Amédé Ardoin Project, a series of fundraisers, seeks to build a public memorial to Ardoin in his hometown of Eunice. An estimated $30,000 to $50,000 is needed for the bronze statue.

Fans of Ardoin and interested persons can host “Amédé home visits,” gatherings that can include readings from former state poet laureate Darrell Bourque and his new book of poetry, “if you abandon me – comment je vas faire: An Amédé Ardoin Songbook.”

Pat Cravins, an actress, speaker and the head of the project’s steering committee, also participates.

Any home that raises $300 during a visit will receive a yard sign that says “Amédé stopped here on his way home.” Proceeds from all visits and book and T-shirt sales will be donated to the project. NUNU Arts and Culture Collective, a 501(c)(3) non-profit arts organization in Arnaudville, will serve as a repository for collected funds.

This new project boosts an everlasting fascination with Ardoin’s music, life and influence. In the 1920s and ‘30s, Ardoin and fiddler Dennis McGee recorded French waltzes and two steps that planted the seeds for Cajun music and zydeco.

Although he was unable to read and write, Ardoin developed a complex and moving accordion style that few can imitate today. His songs of loneliness, heartache and life as an orphan made women break down in the dancehall.

Ardoin’s spirited music also contributed to his end. After using a white woman’s handkerchief to wipe his brow at a dance, Ardoin suffered a severe beating that left him unable to care for himself. He was eventually committed to the state hospital in Pineville, where he died on Nov. 3, 1942. Hospital records list him as case no. 13387.

Ardoin’s life and death inspired Bourque to give voices, through poetry, to those involved. Bourque’s 14 poems lends a personae to Dennis McGee, Aurelia Clint (Ardoin’s mother), even the criminals who beat him.

“The last poem is a found sonnet and all 14 lines are from Amédé’s songs,” said Bourque. “It’s the only poem written in the book in French. There’s not an original words in the poem. Each one comes from one of Amédé’s songs.”

Bourque admires Ardoin’s undying influence, which grows stronger more than 70 years after his death.

“He had an idea of who he wanted to be, in an uncompromised way, musically and personally. Even if it cost him his mind and his life, he wouldn’t turn his back on it.

“That’s such an incredible thing to me. I think Amédé is our Van Gogh, our Camille Claudel, Clementine Hunter. He was an artist who had an idea of how he wanted his life and art to work and he was uncompromised.”

Herman Fuselier is music and entertainment writer for the Daily Advertiser and Times of Acadiana in Lafayette, La. Contact him at bboogie@bellsouth.net.