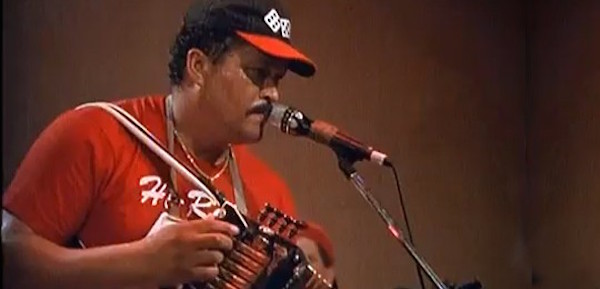

When I first heard Beau Jocque in 1992 at the Quarterback Lounge in a rundown neighborhood of Lafayette, Louisiana, I felt as if I had been transported to a primeval moment in which all the music I loved—funk, blues, R&B and zydeco— had coalesced into a single, relentless groove. I was also a little bit scared.

Here was man with a linebacker’s build, leering into the dark club and singing with a gruff-voiced intensity that could only be compared to Howlin’ Wolf or James Brown, goading his band-mates to shout back at him. As the energy of his performance intensified, the double bellows of his small diatonic accordion, which looked like a toy in his large hands, seemed in danger of being ripped to pieces.

Beau Jocque’s onstage persona was a dramatic contrast to the measured and soft-spoken man I had met on the phone a few weeks earlier. The late Kermon Richard, the owner of Richard’s Club in rural Lawtell, Louisiana, had introduced us. “You’d better get down here and record Beau Jocque,” he told me, “Because he’s hot as a firecracker.” Beau Jocque was packing the club with eager young Creole dancers who were often new to zydeco.

Andrus Espre (his real name) was a Creole himself, born to parents of German, African American and Native American heritage (the Coushatta nation has since established “The Largest Casino Resort in Louisiana,” in his hometown of Kinder). His father, Sandrus Espre, played accordion in the tradition of Amédé Ardoin, whose songs are the bedrock of both Creole and Cajun styles. Yet young Andrus paid little attention to his musical heritage until he was injured in a 1988 industrial accident, when a transformer explosion at a chemical plant knocked him from a tower to the ground. He broke his back. Even after a series of surgeries, was told that he might not walk again.

During his recuperation, he began “fooling around” with his father’s accordion. Accompanied by his wife, Michelle, he began attending dances headlined by Boozoo Chavis and Zydeco Force, studying and analyzing the music that made people excited enough to get up and dance. Ultimately, his vision was to fuse the music of his musical heroes such as War, James Brown and Santana with his father’s old-time sound. Then, one day, he got up out of his wheelchair and became Beau Jocque.

By the time we made his first album for Rounder Records, he had found the musicians who would help him realize his vision. His bass player, Chuck Bush, followed his moves with a manic focus, carving out a fluid melodic counterpoint, while his drummer, Steve Charlot, stuck straight to the point, hammering out an unrelenting, “double-kicked” zydeco beat while yammering a constant patter of high-pitched vocal asides. With guitar player Ray Johnson and rubboard player Wilfred Pierre in tow, the band never wasted a note on anything that did not contribute to the groove.

We rehearsed for the album at Richard’s Club. The next day, my small rental car was barreling along US Highway 190 at 80 miles an hour, on the two-lane bridge that crosses the Atchafalaya Basin. Chuck rode with me, and we were trying to keep up with Beau Jocque. A few months earlier, I had been cited for going 57 miles per hour on the same road. I gave the policeman my Louisiana Colonel card, which had been bestowed on me by Governor Edwin Edwards for my work in recording Louisiana music, and which I had been told might save me from a ticket, but it made little impression. Now, rocketing along behind Beau Jocque’s trailer and diesel pickup, we seemed to have true immunity from the speed traps.

At Ultrasonic Studio in New Orleans, our recording engineer, David Farrell had already set up microphones by the time we arrived. Once we began rolling tape, he turned to me and said, “I’ve never heard zydeco that sounds like this.” He was right, for Beau Jocque and his mates, especially Chuck Bush, had the ability to improvise grooves and motifs that sent zydeco music to a more freewheeling and funky place than it had been before, and they didn’t choke in the studio. We did a few vocal and percussion overdubs, for I wanted the band to shout back in the same way they had at the Quarterback Lounge, and in eight hours, the record was done.

“Give Him Cornbread,” based on the traditional “Shortnin’ Bread,” was an immediate hit on radio stations between Lafayette and Houston. At Richard’s, cars were now lined up along the highway for half a mile in each direction. It would be difficult to imagine a more sublime musical experience than hearing the band in that low-ceilinged club, with the dance floor pulsing up and down with the beat. At every backyard barbeque and crawfish boil, the song blared from radios and beat boxes. At the 1994 Zydeco Festival in Plaisance, fans pelted the stage with corn bread. Beau Jocque was interviewed on WHYY’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross, followed by an appearance on Late Night with Conan O’Brien. His rivalry with Boozoo Chavis, like that of two professional wrestlers, was documented in Robert Mugge’s film, The Kingdom of Zydeco.

By the time we made our fourth album, Gonna Take You Downtown, keyboard player Mike Lockett and guitarist Russell “Sly” Dorion had joined the Zydeco Hi-Rollers, and Beau Jocque had mastered the three- and five-row button accordions. The band hit a musical peak that, to my ears, transcended genre. They might well have been the funkiest dance band in the land.

While traveling with a Rounder Records package tour in 1995, with Marcia Ball and Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys, Beau Jocque suffered a heart attack in Austin, Texas. I met him when he returned home to Kinder, when I took the perhaps audacious initiative of cooking him a heart-healthy meal. Local radio stations had announced that he had died, and while we were shopping in the supermarket in Kinder, the mayor arrived to disbelievingly pump his hand. “Beau Jocque, we thought you was dead,” but the character of Beau Jocque, created in just a few short years by Andrus Espre, was still with us, pushing a shopping cart, ever larger than life.

Beau Jocque had second heart attack in 1999, after returning home from a gig at the Rock’n’Bowl in New Orleans, and this time it was fatal. He left a creative and dynamic void that has yet to be filled, and his influence resonates today in South Louisiana.